Fernando Valenzuela, Who Spent the End of His Career With the St. Louis Cardinals, Does Not Make Hall of Fame

There are baseball legends who shine so brightly that even decades later, their stories feel alive — flickering like stadium lights long after the final out. Fernando Valenzuela is one of those legends. His name alone brings back images of packed ballparks, of fans leaning forward in anticipation, of a young pitcher whose left arm carried not just a team, but an entire city, an entire culture, an entire generation of dreamers.

And yet, this year, when the Hall of Fame ballots were counted and the doors remained closed to him once again, something in the baseball world fell quiet.

It wasn’t outrage.

It wasn’t surprise.

It was something softer — the weight of knowing that one of the game’s most iconic figures continues to stand just outside the place where his story feels like it belongs.

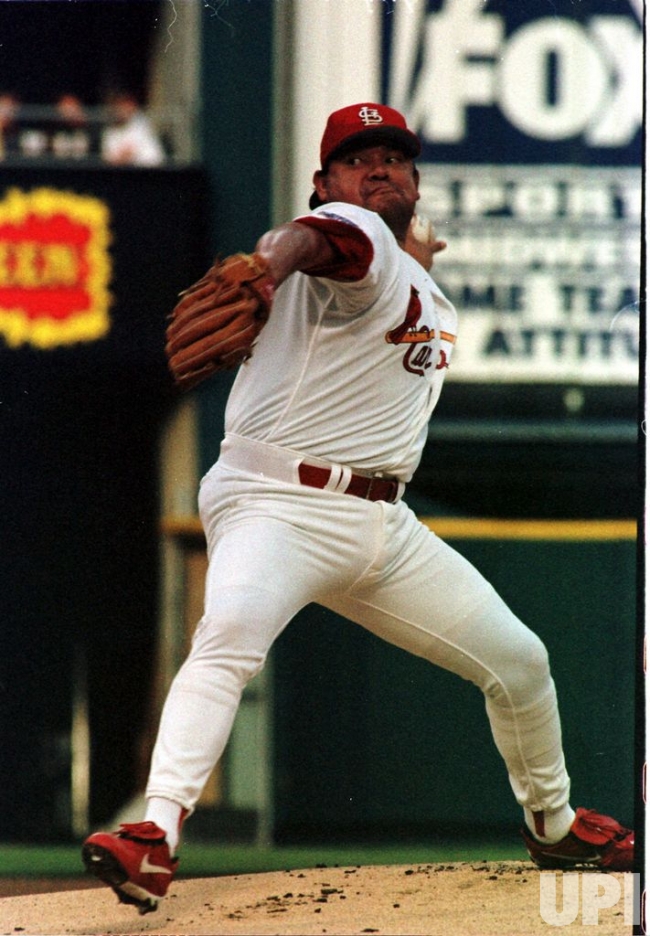

Valenzuela didn’t finish his career with the Dodgers, the team that made him a phenomenon. His journey wound through San Diego, through Philly, through Baltimore, and yes — through St. Louis, where he spent the final stretch of his major league days wearing the Cardinals’ red. Even if his time in St. Louis was short, the appreciation ran deep. Fans understood what he represented. They knew they were watching the closing chapters of a story baseball would never forget.

And now, as that story remains incomplete in Cooperstown, the emotions are complicated.

For many, Valenzuela’s Hall of Fame case is bigger than numbers. It’s bigger than wins, strikeouts, or ERA. Those who lived through “Fernandomania” know that statistics don’t capture the way he changed baseball. They don’t measure the crowds that spilled into Dodger Stadium hours before first pitch. They don’t quantify the families who found themselves represented on a major league mound for the first time. They don’t track how many kids in Los Angeles, Mexico, and beyond picked up a baseball because Fernando showed them they could.

But Cooperstown is a museum of measurements, and measurements can be unforgiving.

So once again, Valenzuela falls short — not for lack of legacy, but for lack of the traditional benchmarks that voters cling to. And while the ballot doesn’t tell the whole story, it still stings to see a player who meant so much to so many remain on the outside looking in.

In St. Louis, fans who watched his late-career appearances remember something different from the dominance of his early years. They remember resilience. A willingness to keep competing, keep grinding, keep pitching when the world believed his best days were behind him. There was dignity in that. Even without the brilliance of his youth, Valenzuela brought a depth of experience that teammates leaned on, a quiet presence that reminded clubhouses what it looked like to love the game without conditions.

Maybe that’s why his absence from the Hall feels so personal: because Fernando Valenzuela didn’t just play baseball — he gave it something. Heart. Identity. Momentum.

And perhaps Cooperstown will someday catch up to that truth.

Baseball history has a way of correcting itself in time.

For now, though, fans across multiple cities — Los Angeles, yes, but also St. Louis, where he finished the journey — share the same bittersweet ache. They celebrate him anyway. They tell the stories anyway. They pass his name down anyway. Because a plaque can honor a career, but it cannot create one. And Valenzuela’s legacy was built in ballparks, not in display cases.

Maybe next year.

Maybe someday.

But even without the Hall’s embrace, Fernando Valenzuela remains one of the game’s immortal figures — not because a committee declared it, but because the people who watched him pitch still feel something when they hear his name.

And sometimes, that’s a greater honor than any bronze plaque could ever hold.